Affected dogs often have periodic vomiting and diarrhoea, lethargy, exercise intolerance, and weight loss. Symptoms come on gradually and become worse with time, but in general it becomes drastic in 3 to 4 weeks time. It can be definitively diagnosed with blood tests. It is thought that there may be an hereditary component to this condition.

In the German Shephard Dog, this illness is considered to have an hereditary component. Research is currently underway to determine if this is also the case in the Leonberger Breed. To learn more about the illness, click above AF Seminar Link to review the Brian Catchpoles seminar. To find out how you can help in the research, see below for these details for AF submissions Information.

In September 2009, the Leonberger Club of Great Britain held a Health Seminar which focused on Anal Furunculosis .We are pleased to announce that the AF Seminar is now available on DVD for purchase through the Club Shop. The DVD contains the morning presentations on AF Treatment and Management and The Genetics Behind AF. A separate web page summarising the seminar is available on this web site.

Anal Furunculosis Research – submissions requests and information

Our research is focussed on identifying genes involved in susceptibility to canine anal furunculosis. We have already identified one set of genes (called the Major Histocompatibility Complex) that are associated with susceptibility, but it is clear that there are other genes involved too.

This information was based on German Shepherd dogs, and it would be really interesting to see if the same association is seen in Leonbergers too.We have also performed a genome wide association study, and identified several other regions of the genome that are associated with anal furunculosis in GSD.

We now need to confirm these regions, and it would make the study much more powerful if we can confirm them in a second breed. All we need is a small amount of blood from which to extract DNA. We would like 1ml of blood collected in an EDTA tube. It can then be posted (at room temperature) direct to me at the address below. Please also enclose the signed consent form plus the filled in AF phenotype form. Initially we would like as many cases as possible, plus any very close relatives that are unaffected.

We would also like 20-30 unaffected that do not have siblings or parents with the disease. But basically any samples will be welcome, so long as we can get the relevant information we need. If anyone has an affected dog that they have not brought to the event, please collect name and address and forward them to:

Jonathan Massey, who will send them a special saliva collection kit. jonathan.massey@manchester.ac.uk

Similarly my colleague Jonathan, will send you some prepaid address forms, if you can tell him where to send them.

Many thanks,

Dr Lorna J Kennedy – Senior Scientist, University of Manchester Centre for Integrated Genomic Medical Research

Stopford Building

Oxford Road

Manchester

M13 9PT

UK Tel: (+44) 161 275 7316

Fax: (+44) 161 275 1617

Email: Lorna.Kennedy@manchester.ac.uk

FCP (fragmented or ununited coronoid process), OCD (Osteochondritis Dissecans) and UAP (Ununited anconeal process). Studies show that although environmental factors can influence the severity of the disease it has a high hereditability rate confirming that a high proportion of the cause is genetic. If we breed only from Leonbergers with minimal ED (The KC and the Club recommend scores of 0 or 1 only) this will help minimise those dogs that will suffer from this in the future. So what do all these terms mean and how do they affect a dog?

- FCP: Fragmentation of the coronoid process can happen as early as 6 months of age if not before. It is the degeneration of the Ulna bone, which breaks up to expose the underlying tissue of the bone. It is seen mostly in the larger breeds of dog and is thought to have a strong genetic transmission rate.

- OCD: Osteochondritis dissecans is the third part of the disorders that make up elbow Dysplasia. It is also a common problem of the shoulder in young rapidly growing larger breeds. With OCD a portion of the cartilage loosens from the underlying bone. It may break loose and float free or remain partially attached like a flap. In either case it is extremely painful as the lower bony layers are exposed to trauma and joint fluid. Dogs with elbow dysplasia will usually limp, may hold the leg away from the body and may try not to place any weight on the affected limb at all. Early signs may be seen from 4 months of age, 6 – 12 months of age show the worst of the symptoms, and with age permanent arthritic changes will occur in the joint. Treatment can be by operating on the affected joint or by the use of medication to make the animal more comfortable.

- UAP: Ununited anconeal process is when the hook part of bone never attaches correctly to the rest of the Ulna as the puppy is developing and floats loose. This leads to joint instability and stops the ulna and humerus interacting properly. It can lead to bruising and irritation of the bones.

X-raying of the elbows will tell if the condition is present. When done after 12 months of age this x-ray can then be sent to the BVA for scoring to see if elbow dysplasia is present. The KC, BVA and LCGB state that only dogs with a score of 0 or 1 should be bred with, as this will help reduce and eliminate the occurrence of this disease which can only be in the best interest of Leonbergers.

A cataract is any opacity of the lens – it can be of any size from pinhead to total lens involvement. It may affect one or both eyes and there are many causes of cataract development. For example an internal inflammation of the eye may result in cataract formation and it is the ophthalmologist’s job to define the cause. Sadly there are currently some 21 breeds of dog in the UK in which the cataract seen may be inherited, usually as a recessive trait, and one of those breeds is the Leonberger.

Now, I’ve said there can be many causes for cataract formation, so how do we know your breed has this disease? I’ve also said that it is the job of the ophthalmologist to define the cause on the basis of his clinical examination – so what is he looking for? Well, primarily it’s the pattern of the cataract inside the lens which dictates the diagnosis, but the ophthalmologist also checks the rest of the eye for any other feature which may indicate any other possible cause. The age at which the cataract makes it’s appearance is also significant and in the Leonberger the disease is seen mainly in the young adult. However, it may occur as early as 6 months of age or as late as 8 years of age. It is not sex-linked but currently there is insufficient data to be certain of the mode of inheritance. However, it is very similar to the cataract seen in the Labrador and this we believe to be a recessive trait.

So let’s have a look at your breed. The cataract is seen primarily as a posterior polar, subcapsular opacity, usually in both eyes. That means that occasionally only one lens may be affected. It is also possible that the appearance of the cataract may differ between the two eyes of the same dog in terms of extent and density, but this is the exception rather than the rule. Usually the cataract is confined to the back half of the lens, but occasionally the whole lens can become involved. So it’s the characteristic appearance that makes diagnosis relatively straightforward. What the ophthalmologist sees is a typically triangular shaped whitish/greyish patch at the back of the lens (i.e. posterior), in a central position (i.e. polar) and within the substance of the lens, not on its external surface or capsule (i.e. subcapsular). However, the mildest example can be a small accumulation of whitish specks flecks in the same region of the lens. Sometimes the classical triangular patch is more round or stellate in shape, and there can be opaque extensions into the lens material around this patch. Actual small fluid filled spaces (vacuoles) may also be seen i.e. round the patch.

These cataracts are seen quite readily once the pupil has been dilated (the pupil is the hole in the iris behind which the lens is found). Any cataract is spotted using an ophthalmoscope and its detail is further described using an instrument called a slit lamp. Often a cataract may be seen with the naked eye as it stands out against the background of the coloured part of the retina. The use of the “drops” (a drug which is short acting and harmless) is an essential part of the examination procedure, the drug taking 20 minutes to dilate the pupil fully. Already there are DNA based tests for inherited cataract in other breeds and I expect a test will appear for your breed in the not too distant future. In the meantime it is most essential that you continue testing your stock through the BVA/KC/ISDS scheme – this scheme is based on annual clinical examination and from the affected results you can work out where the carriers are in the pedigree. A one-off DNA test will be really useful when it arrives, but for the moment you must rely on the ophthalmologist and his ophthalmoscope.

Peter G C Bedford – BVA Eye Panellist

The British Veterinary Association in collaboration with the UK Kennel Club provides breeders with an eye testing scheme to screen for inherited eye disease. By doing so, breeders can help to reduce and ultimately eliminate the frequency of eye diseases being passed on to puppies. Leonbergers are currently on the BVA / KC Schedule A List of breeds under investigation.

In accordance with the LCGB Breeders’ Code of Ethics, all breeding dogs and bitches should be screen at 18 month intervals for signs of Inherited Cataracts.

Breeding dogs and bitches should also be screened every 3 years for a condition called Goniodysgenesis, that can predispose a dog to developing Glaucoma, which is a painful condition that often leads to destruction of the eye.

In both forms, glaucoma results from reduced drainage of the fluid (aqueous humour) that is produced within the eye, resulting in a build-up of intraocular pressure(IOP) which, in turn, leads to pain and blindness. For PCAG/PACG (but not POAG), a screening technique called gonioscopy can identify dogs at risk.

Primary Glaucoma & Goniodysgenesis in Leonbergers

Primary closed angle glaucoma (PCAG) is significantly associated with defective development of the drainage angle which is termed goniodysgenesis (gonio = angle, dysgenesis = defective development). Goniodysgenesis is inherited in several breeds and is tested for using a technique called gonioscopy. It was originally believed that the degree of goniodysgenesis did not progress after birth and so a ‘one-off’ test before breeding was advised for dogs of certified breeds. However, recent research has provided evidence of progression of goniodysgenesis with age in several breeds, namely the Flat Coated Retriever, Welsh Springer Spaniel, Dandie Dinmont Terrier, Basset Hound and Leonberger. In consequence, the advice on gonioscopy has been updated for all breeds in which gonioscopy is performed.

It is advised that for Schedule A breeds gonioscopy should be carried out every 3 years, unless any evidence to the contrary emerges. The first test can be performed in dogs of 6 months or older.

A simple grading scheme (0-3) for gonioscopy was agreed by the Eye Panel Working Party in 2016 and was formally adopted from January 1st 2018. The grading scheme is used to complement the ‘Clinically Unaffected’ or ‘Clinically Affected’ classification of the results of examination. Dogs classified as a Grade 3 “Clinically Affected” should NOT be used for breeding.

| Grade | Gonioscopic findings | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal iridocorneal angle (ICA) with no/minimal pectinate ligament dysplasia (PLD) | Clinically Unaffected |

| 1 | 1-25% of ICA affected by PLD | Clinically Unaffected |

| 2 | 26-75% of ICA affected by PLD | Clinically Unaffected |

| 3 | >75% of ICA affected, and/or severe narrowing of ICA | Clinically Affected |

A report by Georgina V. Fricker, Kerry Smith and David J. Gould entitled “Survey of the incidence of pectinate ligament dysplasia and glaucoma in the UK Leonberger population.” was published in the Veterinary Ophthalmology journal in March 2015 and can be viewed by clicking on the title (in bold above).

The British Veterinary Association in collaboration with the UK Kennel Club provides breeders with an eye testing scheme to screen for inherited eye disease. By doing so, breeders can help to reduce and ultimately eliminate the frequency of eye diseases being passed on to puppies. Leonbergers are currently on the BVA / KC Schedule A List of breeds under investigation.

In accordance with the LCGB Breeders’ Code of Ethics, all breeding dogs and bitches should be screen at 18 month intervals for signs of Inherited Cataracts.

Breeding dogs and bitches should also be screened every 3 years for a condition called Goniodysgenesis, that can predispose a dog to developing Glaucoma, which is a painful condition that often leads to destruction of the eye.

In addition, the entire stomach sack, for reasons not clearly understood, can flip over or rotate into a new position that pinches off both ends, causes a critical emergency. If not corrected swiftly, the ever expanding gases and loss of blood supply to the stomach can lead to rapid decline, shock and death.

The symptoms of canine bloat can be difficult to spot easily.

- Your dog’s abdominal area will be swollen, but it may be difficult to notice.

- He will also pant and salivate excessively.

- Dogs with canine bloat will also walk around agitated, may find it difficult to lay down, and may whine.

- Some dogs also retch or vomit, although nothing will come up.

It is important for owners of deep chested dogs such as the Leonberger to be aware of this serious condition, to know the signs, and to have the details of a 24 hour emergency vet on hand at all times, in case of such an emergency.

There is a Youtube video which you can view showing an Akita with the initial signs of bloat – the dog did receive treatment and survived, but this video provides a very graphic illustration of what a bloating dog looks like and how it acts.

Hip Dysplasia is a widespread condition that primarily affects large and giant breeds. There is a strong genetic link between parents that have HD and the incidence of this in their offspring. We therefore need to take great care when deciding on whether or not to breed from our Leonbergers.

The scores of as many generations as possible for both parents should be examined to see what scores have been achieved. Using breeding stock with consistently low scores will help reduce the incidence of HD and maintain the lowest scores possible.

Other factors such as environment, feeding and exercise can influence the severity of HD but when it comes to preventing the formation of the disease there is only one thing that researchers agree on: selective breeding is crucial. It is therefore very important to breed from dogs with low hip scores.

A one off x-ray after a minimum of 12 months of age can be sent for scoring by the BVA / KC. Hip Dysplasia is made up of joint looseness (when the cup and ball do not fit properly together) which causes joint erosion which can be followed by new bone formation all of which can lead to inflammation and pain.

Depending on the individual dog this may or may not be noticeable to the owner. The pain threshold of the dog and the severity of the condition will affect the animal in different ways. Some show no signs of lameness others do, some will have difficulty in standing up others won’t. There is no way of telling if the condition is present and if so the severity of the condition without x-ray.

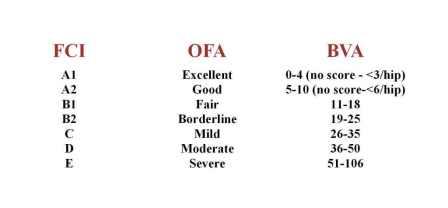

The KC / BVA have a scoring scheme which can then assess the individual giving a score from 0 (perfection) to 106 (has this dog got hips!). At present the Code of Ethics of the Club states that only those with a score of less than 25 (15 max on one side) should be bred with; the breed average score is presently 11. This is taken from the latest available KC/BVA results (for 15 years to 2013) when 1,534 dogs had been scored with results ranging from 0 – 89.

The KC say that breeders wishing to control HD should use dogs with scores below the breed mean average. Remember however that this is only one factor to consider when breeding, elbow scores and clear eyes should also be included in the melting pot and it is no use breeding from animals that meet all these criteria if they are not good examples of breed type with excellent characters. It is no use having a 0 scores for elbows and hips if the result does not look like a Leonberger. This is the quandary faced by all who breed.

There are two main causes of HD, one is genetic and the other environmental. These are said to be equally responsible for HD being present in a dog. Although the genetic code passed on by ancestors has a direct influence on the likelihood of offspring having the disease, the way a pup is reared can influence whether or not it develops HD.

Obesity can cause the bones to erode as the carrying of excess weight on fragile new bones can exacerbate the problem. It is thought that feeding a correctly balanced puppy food in the right quantities is the best way to help promote proper bone growth, these have the specific amounts of calcium, phosphorus and protein needed by pups and will help maintain the optimum body weight if not overfed.

Excessive exercise can also increase the incidence of HD in the young (especially big boned, heavy pups) but fit well muscled adults will be less likely to develop problems with age, swimming and free running are said to be particularly beneficial for adult animals.

Treatment can either be radical surgery where total hip replacement takes place, this is especially successful in younger animals. The removal of the femoral head can sometimes be considered, otherwise the palliative use of drugs to relieve pain and increase mobility.

Glucosamine and Chondroitin are especially successful in alleviating symptoms and can be used in conjunction with buffered aspirin. These treatments are the last resort, the best possible outcome is to produce HD free dogs in the first place!

There are different scoring schemes around the world;

Symptoms may include the development of an overly dry coat or excessive shedding, lethargy and general dullness, weight gain, an increase in blood cholesterol levels, or even anaemia. Once diagnosed, (which may involve two or more stages of specific blood tests), the condition is relatively easily treated through the use of a drug called thyroxine, a synthetic thyroid hormone. This will need to be continued throughout the dogs life.

Although easily treated via an operation, removal of the affected intestine and a short time to heal, the important thing is catching it in first place. Signs of intercusseption are;

- being off food,

- lethargy,

- wanting to pass a stool but not being able too,

- a temperature,

- lack of activity in general.

In particular, these symptoms can be see after a period of Diarrhoea. This condition is difficult to detect to the untrained eye and often the professionals can’t find it until they operate.

To shed some further light n this very rare but critical condition, The LCGB Health Sub-Committee contacted Dr. Benito De La Puerta, a veterinary surgeon at the Royal Veterinary College’s Queen Mother Hospital, who has had experience in correcting this condition in very young pups, in our own breed and others. He kindly agreed to answer a few basic questions about this, particularly in relation to worming treatment, about which some breeders have expressed concerns.

Q- Do you see any patterns of susceptibility in certain breeds or groups of breeds, such as more commonly in large dogs?

Do you see any signs of breed or familial predispositions in this condition?

A- As much as I am aware there is not a breed predisposition but it has been described more commonly in German shepherds. Although it would be something to look into, by keeping a record of all the cases seen in your kennel club. It is slightly more commonly seen in mid to large sized breeds, but can occur in any.

Q- What are thought to be the common causes?

A- Enteritis (inflammation of the intestines) secondary to parasites, viruses (parvovirus), foreign bodies, intestinal masses, previous surgeries, in older dogs often associated with tumor, but in a lot of cases we never discover the cause. Anything that has the potential to affect the rate of motility within the intestines can be suspected.

Q – Do you see any pattern of intussusception occurring following worming, which we have some circumstantial evidence of in our breed?

A – Not that I am aware of. (have found nothing in the literature to indicate this). A worm burden itself is however one known cause.

Q – In the case of worming, what would you recommend in terms of what sort of wormer to use; whether to give on a full or empty belly; whether worming treatment in the mother has any impact in terms of passing on worming treatment to the pups; etc?

A – The best thing is to follow the guidelines given by the worming companies, but I would always recommend administering worming tablets that are prescribed by your veterinary practitioner and not by the ones you can obtain in supermarkets. And always follow a good worming protocol including all the dogs in your household, to decrease the parasite burden.

Q – What is the most common age-range in these cases; very young pups (less than 4 months) or older? What are the signs we should be looking out for?

A – There is a much higher incidence in puppies than in adult dogs. Being more common from eight weeks to one year. Signs: not very specific, Vomiting, depression, anorexia, diarrhea.

Q – Is there any literature on this condition you could recommend to us, particularly any research on breeds, ages, cases that might be helpful to our members?

A – A good web page to access scientific information is Pubmed. I have done a search and there are no papers looking at a specific breed at this time, probably there are not enough cases. There are quite a few scientific papers but looking more into different treatment outcomes, they are not going to give much more information.

Every dog already has a number of micro organisms present within the upper respiratory tract, one of these is Bordetella Bronchisseptica, which when exposed to certain viruses can develop into various upper respiratory disease. Infection occurs from direct dog-to-dog contact or aerosol transmissions (sneezing or coughing) of microorganisms. This means that both a virus and a bacteria acting together are the cause of CCRD.

The type of virus involved governs the type of symptoms presented and the severity of the disease. Following inhalation the microorganisms rapidly colonise in the lining of the airway. This leads to acute inflammatory reaction within approximately four days of transmission.

The most classic symptom is a dry non-productive cough often induced by excitement, exercise or sudden change in the environmental temperature. Many owners describe a sudden outburst of coughing which induces retching and sometimes vomiting. A clear nasal discharge is usually present and this can, if a secondary bacterial infection takes hold, become a thick mucopurulent discharge. Most dogs usually remain bright and appetite not affected. In some instances, usually those involving individuals that already have compromised immune symptoms (elderly, very young, those on steroids) the condition can develop more serious symptoms as the infection spreads to the lower respiratory system, they can also take much longer to fully recover.

Your vet will usually prescribe antibiotics in those instances to help combat the secondary bacterial infection. Other things you can do to help are the use of Anti-tussants (cough medicine) such as codeine and linctus or benilyn non drowsy. (Always check with your vet first before employing such treatments). Also, for those who are really congested, steam and a little olbas oil is a great help at dilating the airways.

Recovery can be up to 14 days but for those who are more affected it will take longer, months even. Affected dogs should be isolated in the sense that they should not socialise with other dogs until about 5 days after the symptoms have ceased. It is also a kennel club requirement that dogs should not be shown for 21 days after symptoms have ceased if diagnosed with an infectious disease. Be aware that any dog that came into contact with an affected dog 5-7 days before the symptoms developed could also have CCRD, so try and let other owners know so they can also take the necessary precautions.

This disease is rarely life threatening but can be quite unpleasant. There are now a number of vaccines available to aid in the prevention of CCRD. Some variants of CCRD are covered in your dog’s annual booster given via an injection by your vet. There is also an intra nasal spray. This is a live vaccine that provides more localised immunisation, and lasts between 6-12 months depending on the type of vaccine used.

Vaccination is either a weak or inactivated variant of the disease, that once administered initialises an immune response. This means that if the dog is exposed to a similar microorganism it is able to recognise it and develop the correct antibodies to fight off the disease.

Homoeopathically you can use Kennel Cough nosodes as a prevention, again this is a weaker variant of the actual disease. Whichever preventative measure you choose, bare in mind that none are 100% effective, and occasionally vaccinated dogs still contract the disease. It is however better than nothing at helping prevent what can be a very unpleasant and debilitating condition. Please note that some veterinarians will often advised that a swab be taken to identify the specific type of bacteria associated with an outbreak of kennel cough in order to select an appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Please ensure that any cough medicine administered is appropriate for use in dogs and that it does not contain Paracetamol, which can be harmful to dogs. Always check with your vet before administering any medications.

LCGB Health Committee (with thanks to Louise McCutcheon)

Despite being very rare in our breed, the LCGB along with the International Leonberger Union are involved in efforts to monitor international Leonberger populations for further evidence of this condition, and in providing information and support where necessary to recognise cases where this condition may be present, and where it is not.

In 2017 a genetic test for this condition was developed by our research partners at the University of Bern in Switzerland and the University of Minnesota in the United States. Their joint research has determined that this is a recessive condition and therefore, individuals who carry a single copy of the affected gene, as well as an unaffected normal copy of the gene will themselves be perfectly healthy and free from any impact.

Furthermore, they may safely be used in breeding programmes so long as care is taken to not match them with other carriers of the defective gene.

This chart illustrates the breeding recommendations for this condition. Any combination that could result in a RED outcome should not be mated together.

| LEMP genotypes of parents |

Average probability LEMP-N/N puppies |

Average probability LEMP-D/N puppies |

Average probability LEMP-D/D puppies |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/N x N/N | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| N/N x D/N | 50% | 50% | 0% |

| N/N x D/D | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| D/N x D/N | 25% | 50% | 25% |

| D/N x D/D | 0% | 50% | 0% |

| D/D x D/D | 0% | 0% | 100% |

The table above is an extract from “LEMP Genetic Test Result Interpretation” by the University Of Minnesota. The full article which includes definitions of the designations N/N, D/N and D/D can be viewed by clicking on the title (in bold above).

In June of 2010 the first genetic marker test for a particularly harsh early onset form, designated as LPN1 was released. LPN1 is suspected to be a recessive illness but this is not as yet known for certain. For further guidance on this, see the Results Interpretation link below.

In 2014 a further genetic test was released for a second, serious form of the illness, designated LPN2. It is believed to be a dominant condition, meaning that a single defective copy of the gene is believed to be sufficient to cause neurological impact in a dog, and therefore, there is no safe carrier status. A dog with either one or two copies is equally vulnerable to developing the illness, on average by their 8th year. The LPN2 test therefore allows breeders to avoid using affected dogs in their breeding programme while they are still young and asymptomatic.

In 2020, the genetic basis for another variant of these conditions was identified and a test was released, this time termed LPPN3, which is found in Leonbergers and some other breeds, most notably Labrador Retrievers. This is believed to be a recessive condition, meaning both parents must pass on the defective gene for a puppy to be affected, and therefore a carrier need not be removed from a breeding programme, so long as it is not matched to another carrier.

It is believed that these three tests, now offered as a single bundle, can be used to screen for over half of all suspected LPN – type neurological conditions that affect our breed. All three are required to be done as pre-breeding tests by the LCGB Breeders’ Code of Ethics. It is known that there is at least one further form of these illnesses that has yet to be identified which accounts for the remainder of cases. The Leonberger Club of Great Britain supports the on-going research aimed at unlocking all forms of polyneuropathy in our breed.

Testing and DNA banking for Leonbergers

This research is being conducted by a partnership consisting of the University of Minnesota in the United States and the University of Bern in Switzerland. Both of these institutions jointly developed the current tests, and are continuing to collaborate on developing further tests on behalf of our breed.

As part of this effort, they have also amassed an impressive DNA sample bank on behalf of the Leonberger breed, which now holds DNA from over 10,000 individual Leonbergers from all around the world. These precious DNA samples have now been put to use for further studies on behalf of our breed including those investigating Cardiac disease, Osteosarcoma and Hemangiosarcoma, among other things.

The LCGB encourages all Leonberger owners to support this important work by donating DNA to the teams in Bern and Minnesota. The best way to do this is to get your Leonbergers tested by these labs directly.

The tests can be done as a single bundle at a very competitive cost and the accuracy of the results are second to none. They are accepted by registry bodies such as the Kennel Club’s own Health database.

Breeding Guidelines

The following charts illustrate the chances that any given puppy in a litter from the indicated mating will have the LPN genotype of N/N, D/N, or D/D. Matings that might result in affected puppies as indicated in red on these charts are not recommended!

| LPN1 genotypes of parents |

Average probability LPN1-N/N puppies |

Average probability LPN1-D/N puppies |

Average probability LNP1-D/D puppies |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/N x N/N | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| N/N x D/N* | 50% | 50% | 0% |

| N/N x D/D | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| D/N x D/N | 25% | 50% | 25% |

| D/N x D/D | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| D/D x D/D | 0% | 0% | 100% |

*We recommend limited use of LPN1-D/N dogs.

| LPN2 genotypes of parents |

Average probability LPN2-N/N puppies |

Average probability LPN2-D/N puppies |

Average probability LNP2-D/D puppies |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/N x N/N | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| N/N x D/N | 50% | 50% | 0% |

| N/N x D/D | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| D/N x D/N | 25% | 50% | 25% |

| D/N x D/D | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| D/D x D/D | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| LPPN3 genotypes of parents |

Average probability LPPN3-N/N puppies |

Average probability LPPN3-D/N puppies |

Average probability LPPN3-D/D puppies |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/N x N/N | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| N/N x D/N | 50% | 50% | 0% |

| N/N x D/D | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| D/N x D/N | 25% | 50% | 25% |

| D/N x D/D | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| D/D x D/D | 0% | 0% | 100% |

The tables above are an extract from “LPN1, LPN2, & LPPN3 Genetic Test Result Interpretation” by the University Of Minnesota. The full article which includes definitions of the designations N/N, D/N and D/D can be viewed by clicking on the title (in bold above).

Panosteitis is sometimes called “wandering lameness” due to the fact that it can affect first one limb, then another, and so on. The first signs of Pano are often a slight lameness in one leg, progressing to a severe limp and possibly non-use of the affected leg. It may last for days to weeks, and may seem to resolve then recur in the same leg, or another one. Some dogs can exhibit lameness in more than one, or even all legs at the same time. Often Pano shows up in a foreleg first. Bouts of lameness can come and go, seemingly for months. Usually, rest and time are advised, although some vets may recommend the use of anti-inflammatory medicines as well. This is referred to as a “self-limiting condition” meaning that it generally resolves itself with no further consequences for the dog once it matures.

If you see the signs of lameness in your young dog, it is advisable to seek veterinary attention to ensure there is nothing more serious going on. Panosteitis symptoms can also be confused with other skeletal and/or muscle problems.

The Signs are thirst, lack of interest in food, malaise, abdominal swelling and vomiting; (unfortunately most of these signs concur with that of the pregnant bitch) also puss like discharge from vulva in an open pyometra. If you have not mated your bitch the signs are more obvious, if you hope she is in whelp you think she is and do not treat her which can be fatal. A scan will show if she is in whelp, usually done at about 4 to 5 weeks into pregnancy and will also show if anything is amiss.

Diagnosis and Treatment is done using blood tests, radiotherapy and ultrasound. Ovariohysterectomy (spaying) is the treatment of choice, but anti-biotic drug therapy can be also successful. It is important to be vigilant for future signs of infection where there has been a previous case not treated by spaying. If you ever have any concerns about the reproductive health of your bitch, please consult your veterinarian.

External Links

This page contains a number of links to external web sites and documents and the Leonberger Club of Great Britian which to make it clear that the links are provided as a convenience, the Club cannot and does not guarantee the availability of the targets and has no responsibility for the contents thereof.